قيرغيستان

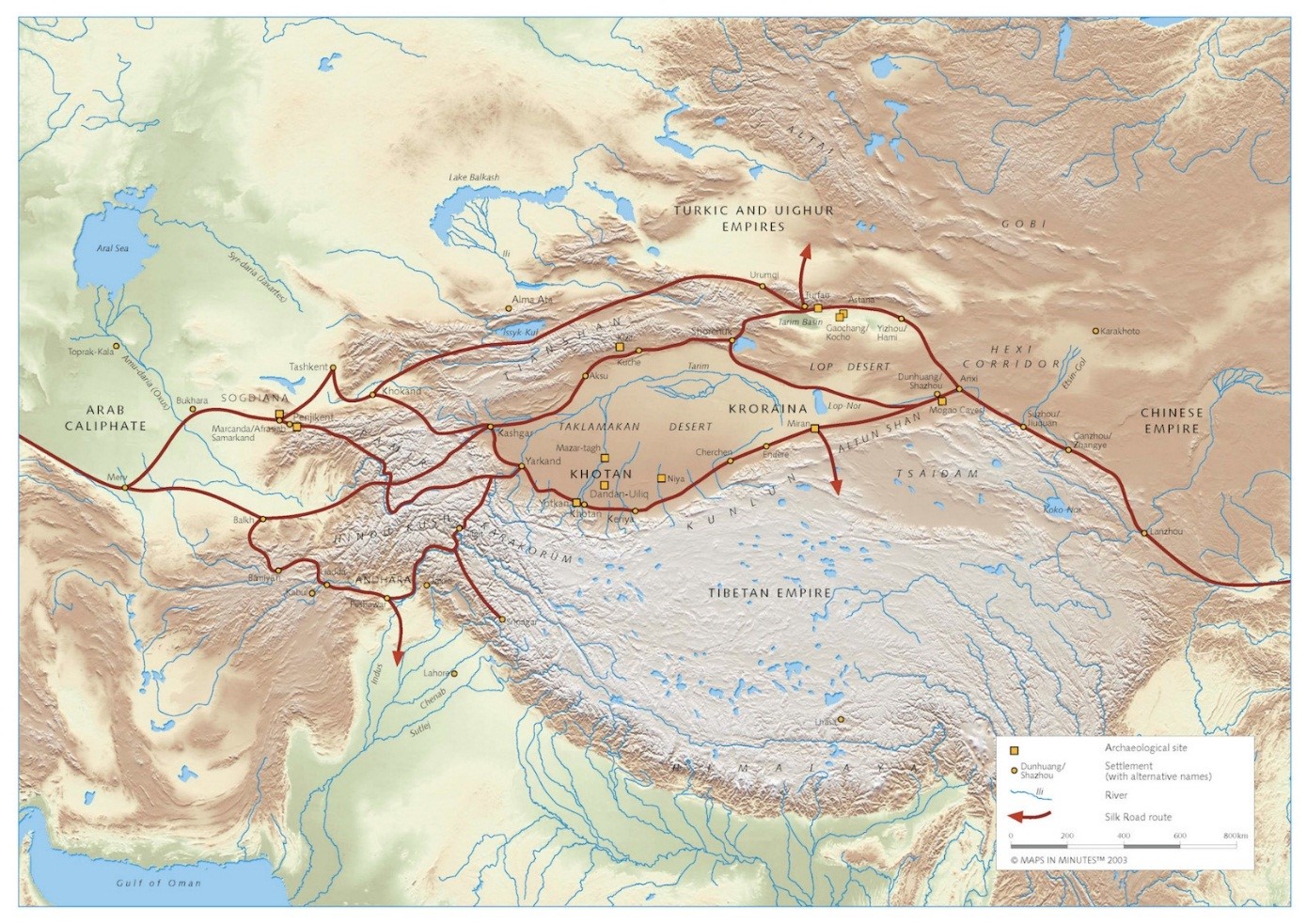

Kyrgyzstan's landscape of high, forested mountains and lush, grassy steppes attracted Silk Roads travelers by its cool climate, sparkling lakes and green valleys after passing perilous, exhausting and arduous western Chinese deserts.

These regions on the main Silk Roads are rich in the ruins of entire cities, trading towns and caravanserais of the Turks, Kyrgyz, Sogdians and other ancient travelers, as well as places linked to the spread of religions such as Zoroastrianism, Buddhist, Christianity and Islam.

Beside the Silk Roads sites and stunning natural beauty, the Silk Roads customs and culture are still alive in Kyrgyzstan in a way that there are still several nomad tribes who live in felt yurts out on the steppes.

The Great Silk Roads glow in the imagination as the world's richest exchange of trade and culture. Caravans of camels, men and horses bore lazurite, silver and spices across thousands of kilometers, but the unseen interaction of ideas and religions was perhaps its greatest glory: enlightening civilizations from Beijing to Rome. Then, as they do now, the lands of Kyrgyzstan remain at an integral crossroads: acting as a gateway for those travelling both East and West on the Silk Roads.

This great moving bazaar was a complex labyrinth of trails that stretched over some of the world's most perilous deserts and mountains. Caravans, a hundred strong, survived the treacherous Taklamakan Desert - found in present day China - and the onslaughts of bandits and slave raiders, only to risk the steep climb over the icy Torugart and Kok Art Passes into Kyrgyzstan.

Here, the Tash Rabat caravanserai bears solitary witness to these extraordinary feats of blood, sweat and bravery.

The current structure dates to the 14th century, although the site on which the structure is found is said to have been occupied since the 10th century.

Extraordinarily atmospheric, the valley now welcomes a new wave of visitors - now travelers - but still echoes the footsteps of Silk Roads traders.

Kyrgyzstan occupies a region of land where many early contacts between peoples and cultures often took place. Many of these intercultural relationships are exemplified through the presence of numerous important monuments that are representative of the country’s diverse history and culture.

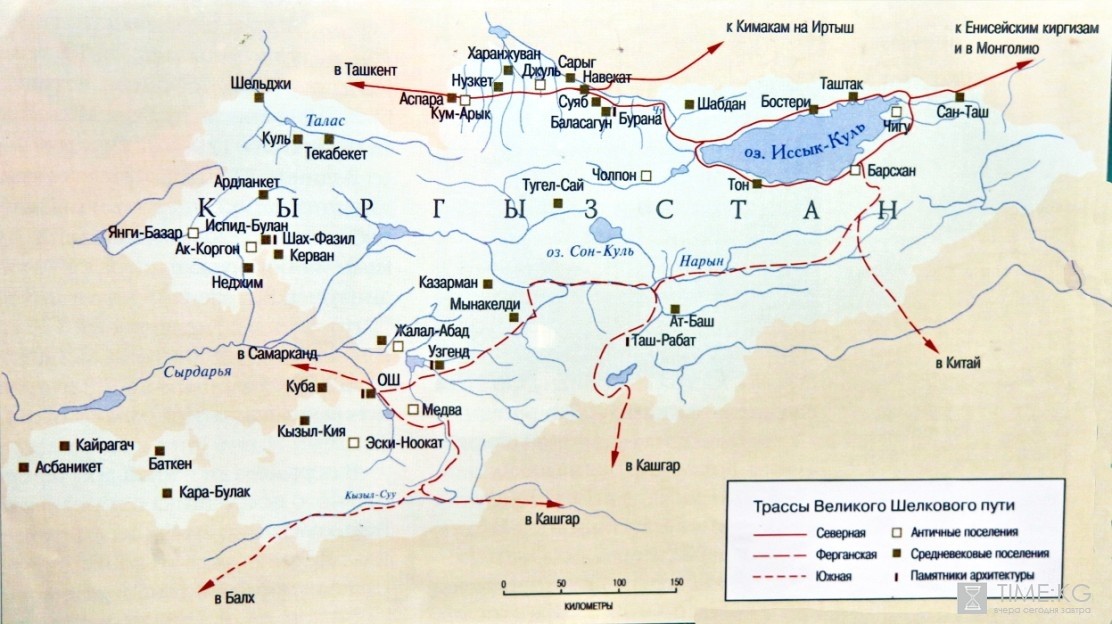

Northern (Fergana) road, which was used in the early Han period, had a special value in Antiquity. A considerable portion of this road passed within what are, today, the administrative borders of Southern Kyrgyzstan, covering the foothill areas of East, Southeast, Southwest and Northwest Fergana Valley. The route went from Kashgar through Terek-Davan pass, to the Alay Valley, along the Gulcha River and its inflows and to the city of Uzgen. It then turned to the Osh Oasis and to West and North Kanguy. It is documented that Zhang Qian travelled this road in 138 BC. This portion of the road is well marked by different sites, especially from Islamic period, when it was described in guidebooks as a transit corridor with two branches:

- through Osh to Medva (Mady) to the South of Alai Valley and further through Terek-Davan and then on to Kashgar;

- from Osh to Uzgen, further through mountain passes, to the valleys of inner Tien-Shan and then splitting into two branches near At-Bashi, the first going through Tash-Rabat and Torugart and passes to Kashgar, and the second, to the Southern coast of Issyk Kul, through Bedel pass then on to Aksuu.

Between the 2nd and 4th centuries AD, the road through Bedel pass and Southern Issyk Kul was already regularly used. It became very actively used during the Early Middle Ages when, due to civil strife in Fergana Valley, caravans began to prefer this route as to the Fergana branch. The most important factor that led travelers of the Silk Roads to favor this path was the presence of Turkic Kagans, who were main consumers of various prestigious goods and who thus supported trade on the Central Asian part of the Silk Roads. A variety of medieval sites – the ancient settlements of Issyk Kul region and Chui and Talas Valleys – are connected with this period: one in which the Silk Roads played an important role in the genesis and functioning of. During the Islamic period, the whole territory of Kyrgyzstan was practically pierced by various parts of separate branches of the Silk Roads. Thus, for the Kyrgyz, these parts of the Silk Roads, representing three chronological periods (Antiquity, Early and Late Middle Ages), were of significant importance. Political, military and economic events of the 8th century considerably reduced the ability of these routes to act as conduits of the Silk Roads – although some revival took place with the political and military rise of Timur and his descendants. However, use of these routes on various parts of the Silk Roads continued until modern age.

Sites of the Southern Issyk-Kul Lake Basin

This portion of the Silk Roads, which functioned throughout the Middle Age, was known as "Hsuan-Tsang's Road" (named after the pilgrim who travelled it in 629 AD). This part of the route is traced by a range of sites and settlements.

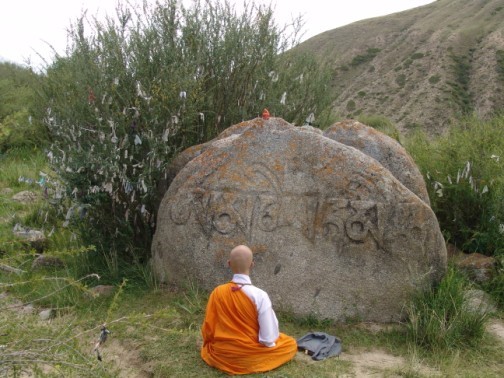

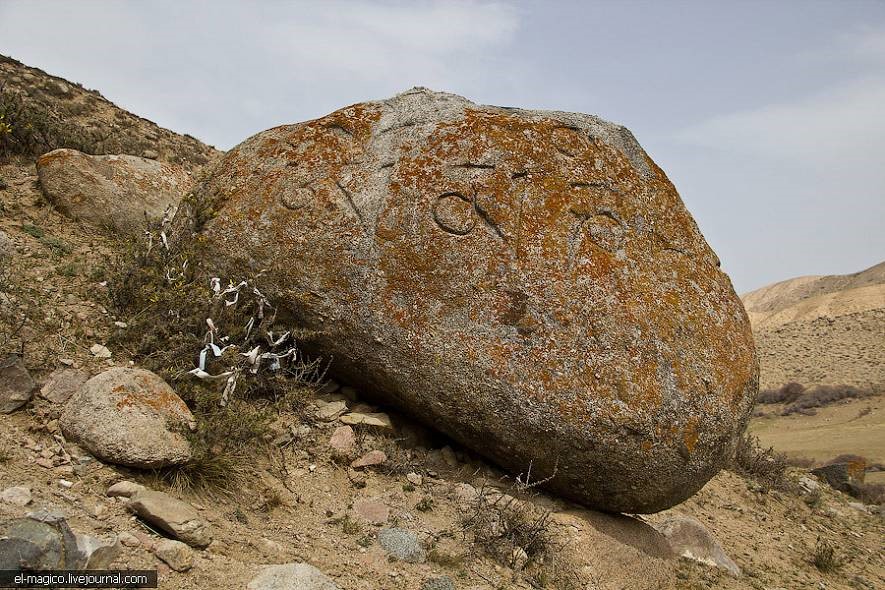

The site of Barskoon is located at the heart of Barskoon Gorge, on the right terrace above the floodplain. It has a 60 meters long square form and is oriented to the cardinal points. Semicircular towers were traced in the corners and centres of the Southern, Western and Northern walls, and the entrance was in the centre of the Eastern wall. The site functioned as a fortress, protecting the entrance and exit from the gorge. The part of the route going through Barskoon and Bedel passes to the area of Aksuu. To the West of this site and 2 kilometers South of the Tamga settlement, there are three stones, dating from the Jungar period (15th-18th centuries AD), with Tibetan inscriptions containing the formula Ohm mani padme hum dated back to Jungar period. Burial grounds from the Turkic period (burial sites with stone sculptures) are located on a floodplain terrace. Sites with Buddhist epigraphs indicate that the Silk Roads caravan routes were known from the Early and Late Middle Ages by pilgrims to Tibet. Now, the local Kyrgyz population considers such sites as mazar, or “sacred place”.

Tibetan inscriptions containing the formula "Ohm mani padme hum”; dated back to Jungar times, 15th-18th centuries AD. Issyk-Kul lake, Kyrgyzstan.

Small settlements are found in the vicinity of the site with some deepness in the gorge, in the direction of Ton pass, which connected Issyk-Kul with Tien Shan and Fergana. Remnants of a defensive wall mark the Western border of the territory of the Upper Barshan, which during the 10th to 12th centuries AD, was another site integral to the functioning of the Silk Roads. It is located on the left bank of the river Ton and to the South of Balykchi-Karakol road. From Ton to the West, the road went along the lakeshore, through a number of settlements. Transit to Chui Valley was made through Boom Gorge.

Medieval Sites in the Upper Chui Valley: Navikat (Krasnaya Rechka), Suyab (Ak Beshim) and Balasagyn (Burana)

All three sites are located along the important branch of the Silk Road, which was functioning in the early and late Middle Ages and served sub-regions of Chui, Issyk Kul, and Southern Kazakhstan.

The main towns of the valley, Navikat (today Krasnaya Rechka), Suyab (Ak Beshim) and Balasagyn (Burana), founded during the 6th century AD, later developed significantly and became unique centres of interdependence between Indian, Chinese, Sogdian and Turkic cultures, as well as a connecting link between these civilizations thanks to their positions on the Northern Silk Roads. People from India, Sogd, Syria, Persia, China and the Northern Steppes settled in the nearby towns, each bringing their own religious and cultural traditions with them. Navikat, and the other towns of the Chui Valley, are mentioned in records left by the Chinese pilgrim Hsuan Tsang, who visited the area in around 620 AD.

Under the Western Turkic and Turgesh Khanates of 560-760 AD, the segment of the Chui Valley situated between Bishkek and Lake Issyk-Kul (40km East of Bishkek) became one of the main political, economic and military centres in Eurasia, connected with Byzantium and China by the Northern Silk Roads. Archaeological excavations carried out in the Chui Valley between 1940 and 2000 discovered towns and monumental constructions dating from the 5th to the 12th centuries that reflected the cultural and artistic traditions of many countries and peoples, from Byzantium in the West to India in the South and China in the East.

The town of Krasnaya Rechka (Navikat) has long been one of the most important of all the urban settlements in the Chui Valley and in the Tien-Shan region. Archaeological excavations in and around the town have revealed a Zoroastrian fire altar and grave site in the Western suburbs, Nestorian Christian votive stones in the citadel and two Buddhist temples south of the town walls. A blend of Turkic, Indian, Sogdian and Chinese cultures can be seen in the materials used in both the religious and civil buildings, constituting a fascinating expression of regional cultural dialogue. Among the early mediaeval Buddhist buildings that have been excavated in the Chui Valley, the second Buddhist temple of Navikat (Krasnaya Rechka) is the only one that has been well preserved.

Ak-Beshim was one of the most important cities in Chui valley. Its remnants are located south of the Chui River and South of present day city of Tokmok, 50 km to the East of Bishkek. According to Chinese and Arab-Persian sources, the town is identified as well-known Suyab Town. The city had 3 areas. The Shakhristan was nearly rectangular, surrounded by massive walls and measured 35 hectares. The southwest corner was marked by the citadel. In the East was a suburb, the Rabad area with slighter walls, which covered 60 hectares. The city walls and buildings were of earthen construction.

Ak-Beshim. Buddhist temple. Reconstruction.

In 1953, archaeologist L.R. Kizlasov excavated several structures. Of these structures almost nothing is left above ground. Two of these excavated structures were Buddhist temples. The Christian church and necropolis dating from the 8th century AD was excavated in the East of Shakhristan. It is one of the most ancient Christian constructions in Central Asia. The archeological and architectural analysis indicates that there was considerable influence of the Asian style (X-shaped plan and domed roof) in its architecture: it is exemplified by its open yard instead of a nave, and the use of pakhsa as a building material. In the southeastern corner of Shakhristan, a complex of Christian churches dating from the 10th and 11th centuries was excavated between 1996 and 1998. This complex is located 10-15 meters away from outer wall and consists of four churches with cross-shaped bema and large halls or courtyards in front of them.

The Burana site is situated 2.5 km east of the village of Donarik. Burana, which rests on the remains of the ancient city of Balasagun, is one of the largest medieval cities in Kyrgyzstan’s Chui Valley. Established in the 10th century on the site of an older settlement, along with Kashgar, Balasagun was one of the capitals of the Eastern Khanate after the Karakhanid state split up. It was saved from destruction by Genghis Khan's Mongols and was renamed Gobalik (good city) in the 8th century, but the city lost its importance and had disappeared by the 15th century.

Burana Tower. Octahedral mausoleum 10 km to the south of Tokmok town. 10th century AD.

There were major archaeological surveys of the site in the 1920s, 1950s and 1970s. The archaeologists discovered that the town had a complicated layout covering some 25-30 square kilometers. There were ruins of a central fortress, some handicraft shops, bazaars, four religious buildings, domestic dwellings, a bathhouse, a plot of arable land and a water main (pipes delivering water from a nearby canyon). Two circles of walls surrounded the town. Although the Karakhanids practiced Islam, they were tolerant of other religions and there are many examples of early Christian (Nestorian) inscriptions. The Burana Museum and Kyrgyz State Historical Museum has some Nestorian gravestones.

Cultural Environment of Manas Ordo, Talas Valley

These sites are located in the northwest of the country, in the upper Talas valley, on the right bank of the Kenkol River, inflow of Talas River, and at the entrance of the Kenkol Gorge. The Silk Roads that went through the sub-regions of Chui and South Kazakhstan connected these sites throughout the Middle Age.

The nearby sites, rife with monuments, provide excellent examples of tangible heritage. The Manas-Ordo Complex, and its nearby vicinity, speaks to the long history of this region, with one example being the barrows of the well-known Kenkol burial ground (dating from the end of the 1st millennia BC to the first half of the 1st millennia AD). Rich archaeological material, including numerous discoveries of silk clothes, demonstrates the presence of relationships with various historical and cultural regions located along the Silk Roads.

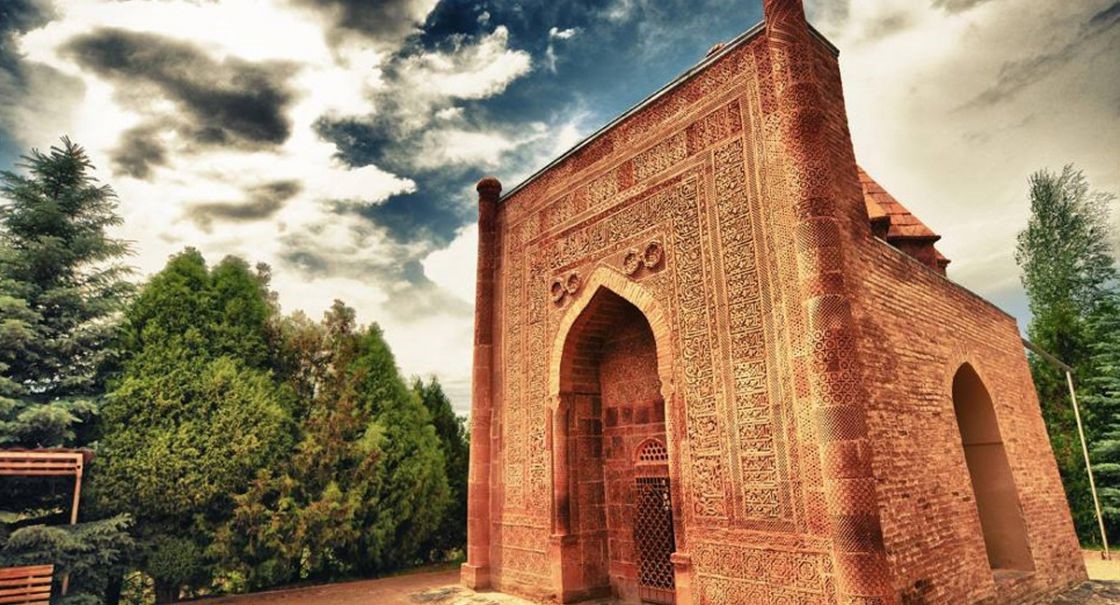

The mausoleum of 14th century AD, a single-chamber, cube-shaped construction with ornamented southern door is another example. The mausoleum belonged to a Chagatai princess, but Kyrgyz people traditionally connect it with the Kyrgyz folk-hero, Manas.

Manas Kumbozu. Architectural monument – mausoleum of 14th century.

Kenkol Gorge is rich in different types of nomadic monuments that date from the early Iron Age to 18th century AD. Petroglyphs and barrows make up a considerable portion of these monuments. Ancient Turkic runic inscriptions were also discovered. Four kilometers to the North-West, one can find one of the largest medieval sites of the valley, Ak-Tobe (Talassky), identified as Tekabket, a well-known site in written sources as “a city at the mountains with silver mines”. The intangible cultural heritage is presented by various rituals and ceremonies connected with initiation of Manaschy – storytellers and narrators of national oral epos Manas—, and also with different pre-Islamic beliefs such as Shamanizm, often presented by cults of tree, water, mountain, fertility and animal-worshiping. For centuries, djailoo, a traditional form of land tenure (ie. use of summer pastures) in Kenkol Gorge, has not changed. It is important that the epos "Manas" remains an active social factor and its influence on modern Kyrgyz society is immense.

Inner Tian-Shan

The peculiarity of this section of Silk Roads is that it served a remote mountainous zone inhabited by nomads. Therefore, it is characterized by lesser number of objects and monuments. A special role in the history of the formation of the road on this territory, belongs to the era of the Turkic Khaganates. It is during this period that the processes of sedentarization of the nomadic population begin, and we see the emergence of cities, settlements and caravanserais in the Inner Tien Shan.

For a region that, for a long time, has been inhabited by nomadic populations, the monuments remaining are of significant importance and a critical number of medieval objects can be found there. These are mainly burial mounds, memorial fences with statues and runic inscriptions, found relatively recently in the Kochkor valley. They are most vividly represented in the districts of Semiz-Bel, Bel-Saz, Besh-Tash-Koro, Suttu-Bulak, Tash-Tube, Kara-Kujur, Jele-Dobo, Kichi-Acha and Chon-Dobo, located in the intermountain tracts and foothills of the Kochkor valley. The main group of the listed types of monuments are objects associated with burial-funeral rites, the rich concentration of which is distinctive to southeastern part of the valley.

Funeral implements, from numerous burial mounds, are represented mainly by: household items, weapons, ornaments and horse harnesses. Occasionally, there are organic artifacts - fragments of leather goods and fabrics, including imported silk items. Next to the burial grounds, fenced rectangular mortuary grounds were built from vertically mounted rock plates. Mortuary grounds had stone sculptures, sometimes replaced by stelae or boulders. Complexes of fences and stone sculptures were erected by relatives of the deceased for the purpose of carrying out memorial rituals.

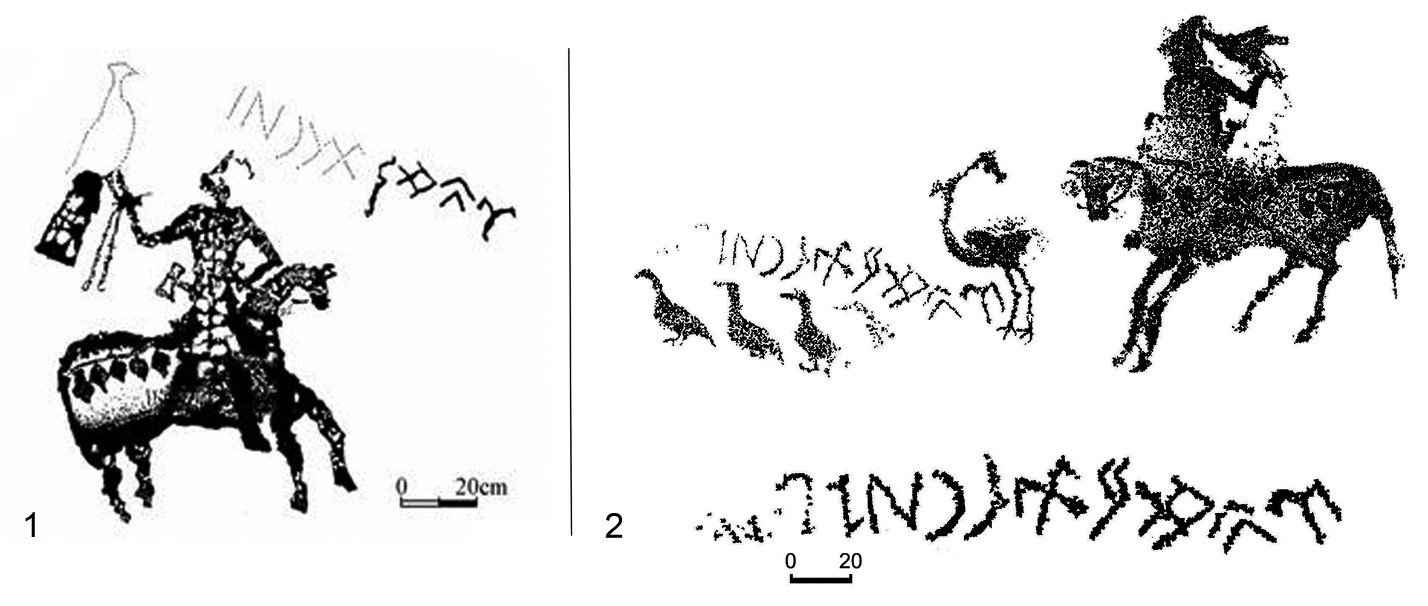

Runic inscriptions

At the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, for the first time, runic inscriptions on boulders were found on the territory of Inner Tien Shan. They are localized at the foot of the Ukok mountain, East of the village of Kochkor, in the Kok-Sai area, on the high terrace of the dry ancient bed. Small part of inscriptions can be found in nearby tracts. In total, twenty-five inscriptions were found, printed with continuous and dotted punching on massive stones, their arrangement is horizontal-linear, with a vertical lettering. Some of them are accompanied by images of a horse, a bird, a goat, a rider on a horse with a hunting bird in his hands. According to experts, the Kochkor epigraphy, like the one in Talas, is left by the Turgesh and is an expression of the right to use land.

Runic inscriptions of Kochkor valley, accompanied with petroglyphs.

Elements of archaic beliefs and environmental culture are manifested by natural mazars adapted to Islam: in particular, the sacred mountains of Kochkor-Ata in Kochkor and Chesh-Tobe in At-Bashi districts. In the region, there are still territories where traditional use of land has been preserved in the form of djailoo-summer pastures and kyshtoo-winter camps. The environmental and climatic conditions of the region, suitable for cattle breeding, predetermined the preservation of many components of traditional livelihood and nomadic way of life, like the local cuisine with specific food processing and cooking techniques; and a variety of handicrafts, ranging from production of nomadic dwellings, such as the manufacturing felt and jewelry to the construction of yurts. The technology of felt making and the production of felted items has been preserved, becoming, today, a separate type of decorative and applied art. Traditional leather processing techniques have not been forgotten either. Traditional hunting methods, which employ the use of Kyrgyz hounds and hunting birds, have been preserved as well. Other types of intangible heritage are seen in toponymy and sanjyra – the oral transmission of genealogy, narrative genre, ritual songs and folk games: all of which echoes the traditional way of life of the Tien Shan nomads and presents its retained relevancy in modern times.

Summarizing the above information on the medieval settlements and sites of the Inner Tien Shan, one can say that, chronologically, all of them arise and function in the Karakhanid era with a few, rare, exceptions. The caravan roads that traversed the region described in the Middle Ages were significant, since they were short routes from Fergana to the Talas and Chui valleys and the Issyk-Kul region, and also to Eastern Turkestan. The Turkic aristocratic environment of the region, being a major consumer of imported goods, provided transport and pack animals, and ensured protection of trade routes within its territories. The aforementioned series of monuments related to the Great Silk Roads is also included in the Kyrgyz Republic's Tentative List of World Heritage.

Ferghana Branch

The Northern (Fergana) road, the initial section that ran through the kingdom of Davan, was of particular importance for the early stages of the functioning of the Silk Roads. Most researchers indicate that this kingdom included the Ferghana Valley and that it was the first Central Asian kingdom where the Chinese envoy Zhang Jian came after fleeing the captivity from Huns in 128 BC. From there, he was transferred to Kanguy. A very brief period of its history, between the 1st and 2nd centuries BC, are well described in Chinese chronicles. In them, Davan is described as a vast agricultural country, in which there are seventy cities and towns. Particularly noted is the cultivation of grapes, from which a large amount of wine was prepared, and mu su grass (also known as lucerne or alfalfa). Records show that there was also cattle breeding and particularly noteworthy was the breeding of thoroughbred horses, the so-called "celestial horses of Davan" that sweated blood after running.

Osh

Osh is Kyrgyzstan’s second-biggest city and the administrative centre of the huge, populous province that engulfs the Fergana Valley on the Kyrgyzstan side. It is one of the region’s genuinely ancient towns with a history dating back to at least the 5th century BC. An important regional centre, around 1 km above sea level, Osh is only 5 km from the Uzbek border and retains a distinctly international and oriental feel. Yet, it is already physically and spiritually closer to Kashgar than to Tashkent. It has the largest mosque in the country and one of the largest and most crowded markets in all of Central Asia. A market town to its very heart, its bazaar has occupied the same spot on the banks of the Akbura River for 2,000 years. The rich history of the oasis, of which much is unknown, lies hidden in the past and little remains to be discovered.

As early as the 8th century AD, Osh became known as an important centre for silk production, as well as a trade centre thanks to its location at a crossroads of different routes along the Silk Roads. Legend states that Alexander the Great visited the city on his way to India, although most legends refer to the Macedonian warrior king. King Solomon is also said to have visited and slept on top of the hill that still bears his name – Taht-i-Suleiman (Suleiman Mountain or Solomon’s Throne). What is more certain is that the founder of the Indian Moghul Dynasty and descendant of Tamerlane, Zahiruddin Muhammad Babur, who was born just across the Uzbekistan border in Andijan, came to Osh to visit Solomon’s Throne before venturing to India.

Of Osh, he wrote in his memoir, the Baburnama:

"There are many sayings about the excellence of Osh. On the southeastern side of the Osh fortress is a well-proportioned mountain called Bara-Koh, where, on its summit, Sultan Mahmud Khan built a pavilion. Farther down, on a spur of the same mountain, I had a porticoed pavilion built in 902 [AD1496-97]. "

Sultan Babur also nostalgically described the city in his memoirs:

"Orchards follow the river on either bank, the trees overhanging the water. Pretty violets grow in the gardens. Osh has running water. It is lovely there in the spring when countless tulips and roses burst into blossom. In the Fergana Valley, no town can match Osh for the fragrance and purity of the air."

From the earliest days of the Silk Roads, Osh acted as a major hub for travelers along these routes. From its earliest days, camel caravans who survived the journey over the high passes of the Pamir Alay to the South and of the central Tien Shan to the East, brought with them their cargos of exotic items, including silk from China, lazurite from modern Tajikistan, sweets and dyes from India, and silver goods from Iran. Between the 10th and 12th centuries, it was the third largest of the great cities of the Fergana Valley. Nothing remains of the palace, courts and academies destroyed in the 13th century by the armies of Genghis Khan. But slowly, Osh recovered and rebuilt itself over the next few centuries and the city went on to become part of the Kokand Khanate in 1762.

Uzgen

Uzgen, a town with at least two thousand years of history, is located 55 km northeast of Osh, on a cliff-top above the wide plain of the Kara-Darya River. It is an ancient settlement, mentioned as the town of Yu in the Chinese chronicles of the 2nd century BC. Uzgen's position along the Silk Roads marked the passage into the Turkic world and a place for pause, thus ensuring that it profited from the side shoots of the Silk Roads. Traders would tally up profits and swap their animals here, bracing themselves for the rigors ahead or recuperating from a completed journey. Its position at the head of a narrow valley also made the town a centre for taxation.

Uzgen reached its zenith under the Karakhanids, being the capital of a loosely knit empire that stretched over both sides of the Tian Shan, and incorporated most of the lands of Transoxiana. It is said that the great Ismael Samani was imprisoned in Uzgen before he managed to escape, disguised in women's clothes. After the Ilek Khan had secured a sufficient power base, the capital was transferred to the centralized town of Samarkand and Uzgen became the residence of the ruler of Ferghana.

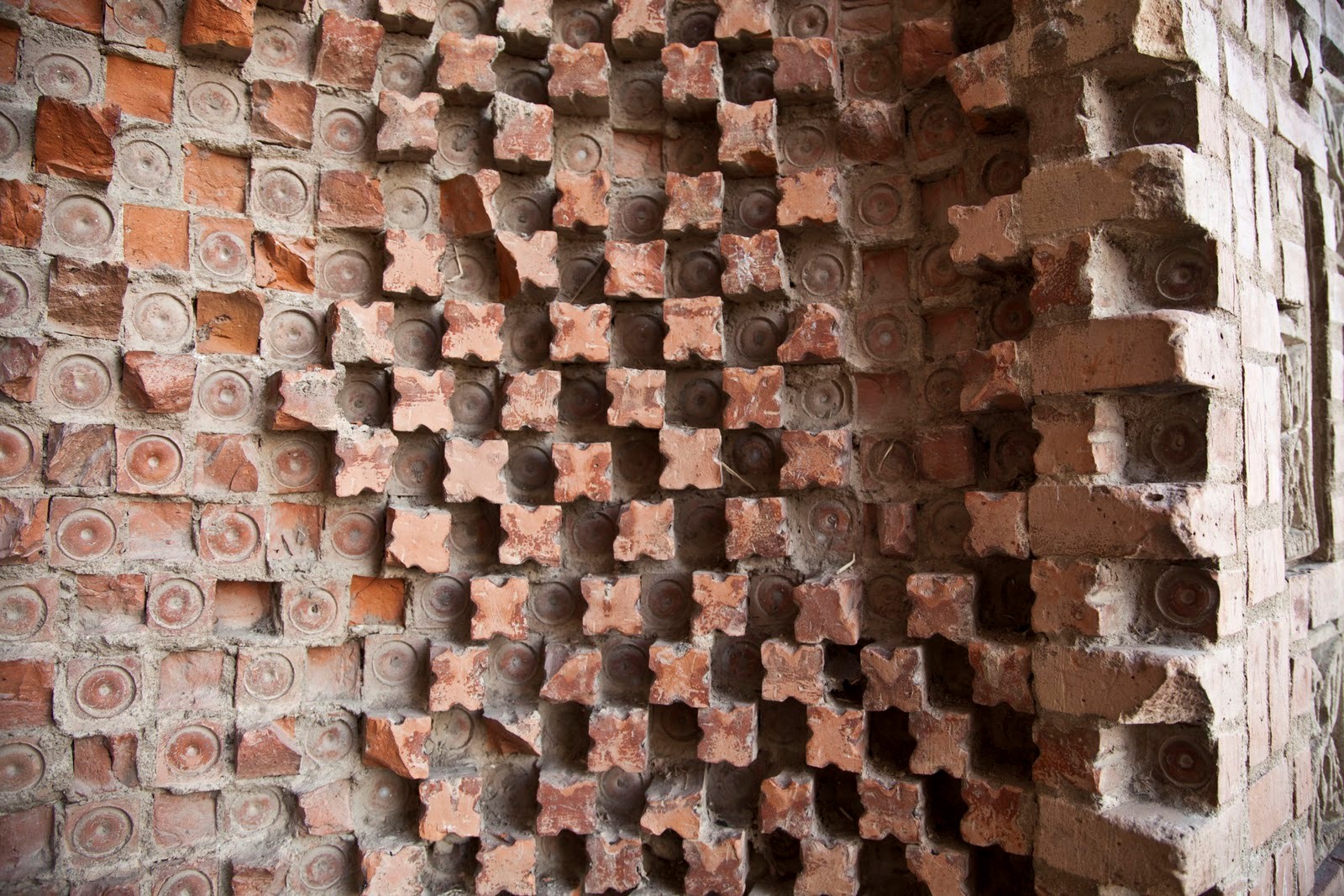

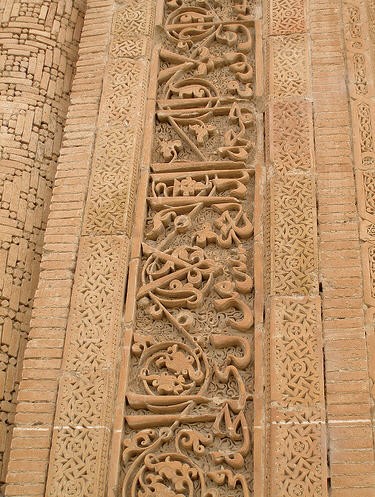

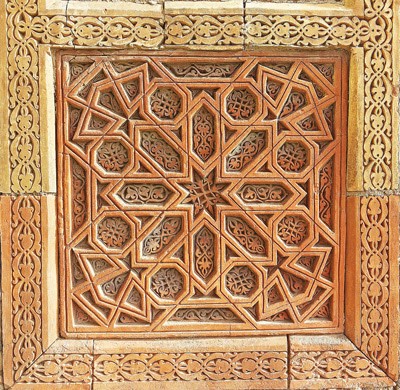

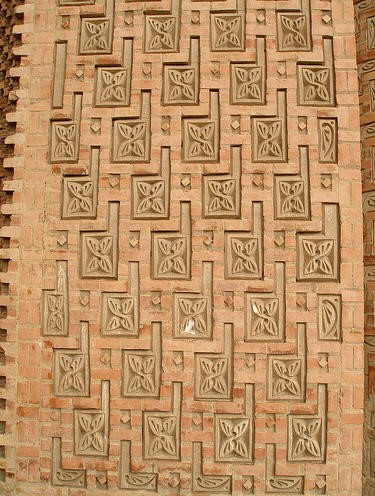

Little of Uzgen's ancient history remains intact, apart from a quartet of Karakhanid buildings: three joined 12th century mausoleums and a stubby, 11th century minaret (the top of which apparently fell down in an earthquake in the 17th century), each faced with very fine ornamental brickwork, carved terracotta and inlays of stone. The small minaret and three mausoleums are mainly notable because of the rarity of pre-Mongol architecture in Central Asia and for the exquisite quality of the tilework. The complex is said to represent an important step in Islamic art, denoting a shift of emphasis from the interior to the exterior.

Each mausoleum is unlike the others, with the exception of them all being made of similar shares of red-brown clay – there were no glazed tiles at this point in Central Asian history). The mausoleums are made with exquisite engravings on terracotta slabs, and relief work of up to three centimeters in depth, and intricately worked terracotta foliage with competing geometric patterns hangs over each mausoleum’s doorways, pillars and facades.

Of the three mausoleums, the central Mazaar of Nasr ibn Ali predates the others by over a century. The portal has been largely restored, but a section of melted girikh to the left still points to its original glory. Tradition associates the tomb with the resting places of the first Karakhanid Khan who died in 1012 AD.

To the left is the Jalal Ad Din Al Hussein Mausoleum, built in 1152. Beautiful foliated Nakhshi calligraphy above the arch contrasts with the less ebullient plaited Kufic above the door and the two are separated by a fine incised terracotta girikh design underneath the arch. The circles to either side of the arch may be an echo of earlier Zoroastrian beliefs.

The most obvious, beautiful and eye-catching designs, however, are reserved for the southern mausoleum (1186) that has incised terracotta plaques and inscriptions that cover every arch and concave of the facade, like some monotone trial run of the Shah-i- Zinda, which it predates by over 200 years.

All three buildings are visited by pilgrims, especially women, who use the tombs as mosques, touching the walls and rubbing their faces as they leave. However, the tombs mostly lie deserted, quietly reflecting the pinkish hue of the ground from which they came.