أوزبكستان

بوابات العبور في مدن أوزبكستان على طول طرق الحرير التاريخية

سمح موقع أوزبكستان الاستراتيجي في قلب القارة الأوراسية لها بلعب دور رئيسي في النظام العابر للقارات لطرق الحرير الكبرى.

في الواقع، مرت الطرق الرئيسية لطرق الحرير الكبرى التي ساهمت في أنشاء الاتصال بين الشرق والغرب عبر أراضي أوزبكستان الحالية، والتي كانت واحدة من الأماكن التي نشأت وتطورت فيها الحضارات الأولى.

تتميز أوزبكستان بخصوبة أراضيها والتي تم تطويرها بشكل مكثف من قبل البشر، أضافة الى تنوع الموارد، ووجود الثقافة المتقدمة، والمستوى العالي لصناعة الحرف اليدوية والعلاقات بين المال والسلع. وهذه هي العوامل التي حثت على نشوء طرق التجارة الرئيسية لطرق الحرير في تلك المدن. يرتبط اكتشاف المناطق الغربية (أي آسيا الوسطى) وتشكيل طرق الحرير الكبرى باسم تشانغ تشيان، الدبلوماسي الصيني، الذي أرسله الإمبراطور وو دي إلى باكتريا عام 138 بعد الميلاد.

كانت مهمة شانغ تشيان إبرام اتفاق مع اليوزي بشأن الإجراءات المشتركة ضد تيانجو معًا. وقد استمرت رحلة تشانغ تشيان بأكملها إلى يوزي لأكثر من 13 عامًا.

على الرغم من أنه لم يستطع إقناع اليوزي بالمشاركة في مشاريع مشتركة، إلا أنه كان لا يزال قادرًا على جمع معلومات عن الدول والشعوب التي تعيش في المناطق الغربية. لذلك، أثارت المعلومات التي حصل عليها تشانغ تشيان اهتمام الإمبراطور وموظفيه، حتى تم أرسال تشانغ تشيان مجددا ليتمكن من فعل المزيد في المنطقة الغربية حيث كان الإمبراطور يعتزم زيادة النفوذ الصيني هناك.

بهذه الطريقة تم تأسيس نظام العلاقات والاتصالات الدولية، والذي سمي فيما بعد باسم طرق الحرير الكبرى. نتيجة لهذه الجهود، تم تأسيس علاقات تجارية وثقافية وثيقة مع أربع قوى عظمى في العالم القديم (إمبراطورية هان، إمبراطورية كوشان، الإمبراطورية البارثية والإمبراطورية الرومانية).

مع مرور الوقت، أصبحت طرق الحرير الكبرى هي الطرق التي لم تقتصر على أنشطة التجارة فحسب، بل تم تأسيس علاقات ثقافية أيضًا.

على طول طرق الحرير العظمى سافر المبشرون الدينيون والعلماء والموسيقيين والعديد من الأفراد الآخرين.

ومع ذلك تجدر الإشارة إلى أن أداء طرق الحرير الكبرى لم يكن دائمًا مستقرًا ودائمًا حيث ارتبط بشكل أساسي بالبيئة السياسية الموجودة في المناطق والبلدان التي مرت بها تلك الطرق

علاوة على ذلك، أظهرت الدراسات التي أجريت على طرق الحرير الكبرى أن طرقها غيرت اتجاهها في فترات مختلفة من التاريخ.

يمكن ملاحظة هذه العملية من خلال مثال الطرق التجارية التي تمر عبر أراضي أوزبكستان الحالية أيضًا.

كما تجدر الإشارة إلى أن دور السغديين في تنمية التجارة الدولية على طول طرق الحرير الكبرى كان كبيرًا، وهو ما أكدته العديد من المصادر المكتوبة والاكتشافات الأثرية التي تمت في الصين وآسيا الوسطى.

بنفس القدر من الأهمية كانت المساهمة التي قدمتها دول أخرى أيضًا، أي التجار من باكتريا ودايوان (دافان) وتشاش (شاش) ذات أهمية ايضا.

ترجع أكثر فترات أنشطة طرق الحرير العظمى في إقليم أوزبكستان الى فترة العصور القديمة؛ عندما أصبحت آسيا الوسطى جزءًا من الخانات التركية؛ خلال العصور الوسطى المتقدمة.

تُظهر الدراسات الاستقصائية والتحريات الأثرية التي أجريت في إقليم أوزبكستان أنها موطن لعشرات مراكز المدن الكبيرة، ذات الصلة بأزمنة العصور الوسطى، التي مر خلالها طريق الحرير العظيم.

ومع ذلك، وبسبب النطاق المحدود للدراسة الحالية، لا يمكننا الخوض في تفاصيلها. لذلك قررنا على دراسة أربع مدن تقع على حدود البلاد، والتي من خلالها تم الاتصال بين هذا الطرق وطرق البلدان المجاورة.

هذه هي مدن Ahsikent (تقع في الشرق) ، Kanka (تقع في الشمال الشرقي ، والحدود مع السهوب البدوية) ، Poykend (تقع في الغرب) و Termez (تقع في الجنوب).

تعتبر يارقاند واحدة من تقاطعات طرق الحرير العظمى المعروفة. هنا تم تقسيم المسار إلى فرعين، الفرعين الشمالي والجنوبي.

الفرع الجنوبي من خلال بامير وبدخشان والذي أدى إلى باكتريا وإلى مدن الشرق الأوسط والبحر الأبيض المتوسط. بينما ذهب الفرع الشمالي من الطريق عبر قاشجار وممرات مختلفة وصولا الى أراضي دايوان (وادي فرغانة)

في بداية الامر كان الطريق من خلال ازوجين الى اوش ومن أوش مرورا بمدن أوزبكستان.

في هذا الصدد، كانت أكبر مدينة في وادي فرغانة، والتي مر بها طريق الحرير العظيم هي أهسيكنت حيث تقع أطلال هذه المدينة على بعد 25 كم إلى الجنوب الغربي من مدينة نامنجان على الضفة اليمنى لنهر سير داريا.

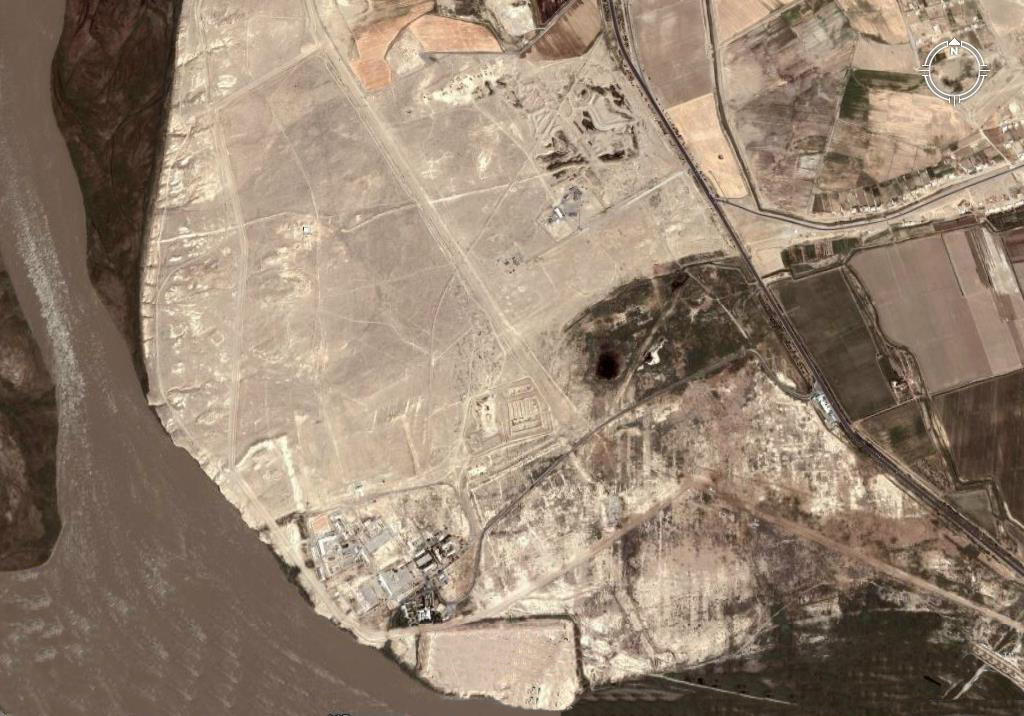

من الناحية الهيكلية، ينقسم الموقع القديم إلى ثلاثة أجزاء: قلعة وشهرستان وربد. المساحة الإجمالية للموقع حوالي 350 هكتار. تم تدمير شرائح فردية من الموقع بواسطة نهر سير داريا في الوقت الحالي.

تقع القلعة في الركن الجنوبي الغربي من الموقع القديم. من الشمال والشمال الشرقي، تتاخم شهرستان، الذي يفصل عنها من خلال خندق عميق.

تتألف شهرستان من جزأين. لم يتم الحفاظ على اسس المدينة باستثناء بعض المناطق الجبلية الفردية. والجدير بالذكر أن مؤسسي المدينة، أثناء بنائها، استخدموا بنجاح خصوصيات التضاريس.

تم حفظ المعلومات القديمة المتعلقة بمدن وادي فرغانة في السجلات التاريخية الصينية كما يمكن العثور على المعلومات المتعلقة بها في المصادر المكتوبة في العصور الوسطى أيضًا.

على الرغم من أن تلك المعلومات ليست مفصلة ومع ذلك، فهي ذات أهمية كبيرة عندما يتعلق الأمر بإعادة بناء التضاريس التاريخية لمدن فرغانة.

في هذا الصدد المثير للاهتمام هو المعلومات التي قدمها ابن حوقل. وقد كتب قائلاً: "فرغانة هو اسم البلد، الذي يمثل مقاطعة شاسعة بها مدن ومستوطنات ثرية. عاصمتها Ahsikent. يوجد بها قلعة، تقع في شهرستان، والتي توجد بالقرب من ربد. يقع قصر الحاكم والزنزانة داخل القلعة. رغم أن المسجد / الكاتدرائية ليس موجودًا ... فإن انتشار المدينة يبلغ حوالي ثلاث فرسخ "(Betger، 1975، pp. 25-26).

من الواضح أن هذه المعلومات ليست كافية لإعادة بناء المظهر التاريخي للمدينة. ونتائج الدراسات الأثرية، في هذا المعنى، يمكن أن تكون حاسمة في العثور على إجابات لهذه الأنواع من الأسئلة.

في الوقت الحاضر تعتبر Ahsikent أحد أكثر النصب الأثرية التي تم دراستها جيدا ضمن وادي فرغانة.

وبالتالي، تم تنفيذ أعمال الحفر في جميع أنحاء هذا الموقع القديم تقريبًا. وأظهرت نتائج الدراسة الأثرية أنه في نهاية القرن الثالث - بداية القرن الثاني قبل الميلاد. بدلا من Ahsikent ظهرت مدينة محصنة جيدا، والتي تبلغ مساحتها الإجمالية 40 هكتار وشملت أراضي القلعة وشهرستان.

بالفعل في القرنين الأول والثاني قبل الميلاد وصل سمك جدرانها إلى 20 م. سمحت هذه المعلومات أن يستنتج أنارباييف أن هذه هي أنقاض عاصمة دايوان (فرغانة)، ارشي والتي ذكرت في المصادر التاريخية الصينية (أنارباييف، 2008، ص 146-147). أصبحت المدينة صالحة للسكن بشكل مكثف في أوائل العصور الوسطى أيضًا. خلال تلك الفترة تحمل اسم "Feghana".

في موقع Ahsikent القديم، تمت دراسة الطبقات المرتبطة بالعصر الإسلامي جيدًا بفضل اكتشاف المباني البلدية والمناطق السكنية والأماكن والمراكز الصناعية. على وجه الخصوص، في إقليم شهرستان، تم اكتشاف بقايا المسجد الكاتدرائية ومنزل الحمام، الذي له هيكل تخطيطي معقد.

أيضا، تم الحصول على بعض المواد المثيرة للاهتمام فيما يتعلق بخطوط الاتصال الحالية وبيئة المعيشة. في نفس الوقت يستحق الاهتمام بشكل خاص نتائج الدراسات التي أجريت في مراكز الحرف اليدوية المتخصصة في إنتاج الصلب الدمشقي. في الواقع، تم الكشف عن العديد من هذه المراكز في هذا الموقع القديم (Anarbaev، 2008). هذه النتائج تشير إلى أن Ahsikent كانت مدينة عمال الصلب والحرفيين، الذين يمثلون أساسها الاقتصادي. من الجدير بالذكر أن الأطباق الزجاجية والسلع المصنوعة من الزجاج، والتي تم تصنيعها هنا، تبرز بجودتها العالية وصقلها، مع تنوعها الغني وتصميمها الفني الأنيق. وبدون أي شك، يمكننا أن نفترض أن جزءًا كبيرًا من منتجات الحرف اليدوية هذه كان مخصصًا للأسواق المحلية والدولية.

تشير نتائج الدراسات إلى أن أهسيكنت كان أكبر مركز سياسي واقتصادي وثقافي لوادي فرغانة في القرنين التاسع عشر والثالث عشر. في ذلك الوقت، صنع سكّان المدينة عملات معدنية بالنيابة عن محافظي سامانيد وكارخانيد. ومع ذلك، سقطت المدينة في الخراب في بداية القرن الثالث عشر، نتيجة للحملة العسكرية للتتار المغول، تم تدمير المدينة بالكامل.

بعد أهسيكنت تحول الطريق وسار على طول نهر سير داريا ومدينة باب إلى خودجينت.

في خودجينت، ذهب أحد فروع هذا الطريق إلى جانب نهر سير داريا، وتوجه إلى الشمال ودخل منطقة السهوب وواحة طشقند.

واحدة من أقدم وأكبر مراكز المدن في تشاتش (واحة طشقند) هي كانكا، وتقع على بعد 70 كم إلى الجنوب الشرقي من طشقند و8 كم إلى الشرق من الضفة اليمنى لسير داريا. كانت المدينة أول عاصمة تشاتش. تأسست كانكا على الضفة اليسرى لنهر اخانجاران، والتي كانت تتدفق ذات يوم إلى سير داريا. المساحة الكلية للموقع القديم لا تقل عن 400 هكتار. وهي تتألف من قلعة محمية بشدة، يبلغ ارتفاعها حيطانها 40 متراً، فضلاً عن ثلاثة من مراكز المدينة وحي التجار والحرفيين، المحصنين بجدران دفاعية قوية.

تضاريس الموقع القديم تسمح بالاطلاع على شوارع المدينة الرئيسية وساحات الأسواق وأحياء الحرف اليدوية والمناطق السكنية الفردية والكرفانات.

كانت كانكا معروفة أيضًا باسم خراشكنت، بمعنى آخر "مدينة فارنا" (معلومة مذكورة في المصادر العربية والفارسية في العصور الوسطى).

الدراسات التخطيطية والخرائطية التي أجريت في موقع كانكا القديم تحت قيادة يياركوف سمحت بتحديد المراحل الرئيسية في تشكيل وتطوير المدينة، وفهم تضاريسها التاريخية.

أظهرت الحفريات أن المدينة ظهرت بدلاً من المستوطنة المنتمية إلى منتصف الألفية الأولى قبل الميلاد والتي كانت مسكونة بشكل مكثف حتى القرن الثاني عشر الميلادي

كانت النواة الأولى للمدينة موجودة بدلاً من القلعة التي تعود للقرون الوسطى، حيث تم العثور على نظام معقد من الجدران الدفاعية وكذلك بعض الأواني الخزفية النموذجية للفترة الهلنستية (بورياكوف ، بوغومولوف ، 2009 ، ص 70).

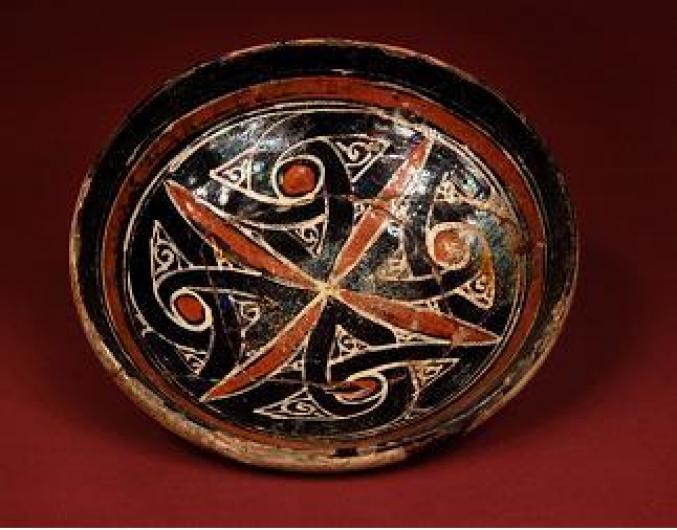

هذه الاكتشافات، إلى جانب المعلومات التي تم الحصول عليها من المصادر القديمة، مكنت العلماء من افتراض أن ظهور المدينة في مكان كانكا مرتبط بحملات ديمودام، جنرال سلوقي ضد الساكا حيث عبر ديمودام نهر ياكسارت (سير داريا) وأسس مدينة أنطاكية تكريماً لحاكم السلوقية وأقام هناك مذبح الكنيسة لأبولو (بورياكوف ، بوغومولوف ، 2009 ، ص 71). ترتبط المرحلة التالية من تطور المدينة بالفترة الحاكمة لولاية كانجو. كانكا تصبح عاصمة في حيازة يوني وكانجو كلها (القرن الثالث قبل الميلاد - القرن الثالث الميلادي). خلال هذه المرحلة، يتم تنفيذ أعمال تخطيط المدينة على نطاق واسع، حيث يتم إنشاء مباني ملكية وعبادة ضخمة في المدينة. علاوة على ذلك، يتم إعطاء صناعة زخرفية جديدة زخما متجددا، وتتوسع مجموعة متنوعة من المنتجات، والعلاقات السلعية والمال تتطور بسرعة. تقوم مدينة شاش بتصنيع العملات المعدنية الخاصة به ، والتي يتم استخدامها خارج حدود المنطقة. في الواقع، هناك كل الأسباب للاعتقاد بأن تصنيع النقود يقع في كانكا بالضبط. تم العثور على عملات الصين وسوغد في كانكا، مما يشير إلى علاقاتها التجارية والثقافية الوثيقة مع الدول المجاورة.

Further growth of the city is associated with its becoming part of Turkic Khanate in the middle of the VI century A.D. Initially Kanka retains its status of political and economic center of Chach Oasis. However, after unsuccessful attempt of the residents of Chach to secede from Western Turkic Khanate in the VIII century A.D., the capital was transferred to the territory of Tashkent (Buryakov and Bogomolov, 2009, p. 73). As a result of this habitable area of the city gets reduced. Nonetheless, the city continues to play the role of large economic center of the region and already by the VIII century the life gets normalized here. Moreover, new manufacturing areas begin to be mastered, associated with different branches of handicrafts. The next stage in the flourishing of the city relates to the XI-XII centuries, i.e. during the ruling period of Samanids and Karakhanids. During this period the city was known as Kharashkent. According to Arabic and Persian sources, it was considered as the second important city from among city centers of Tashkent Oasis after Binkent. During this period the area of the city gets expanded and covers almost 400 ha. If looked from archaeological perspective, it is exactly this time period in the life of the city that is well studied. Thus, the works undertaken shed some light to the planning structure of the city during the last stage of its inhabiting. In particular, a very interesting architectural complex of palace-like nature relating to Karakhanids period was explored in the citadel, residential areas, manufacturing centers and trade shops in the territory of shahristan I and II were studied. Also, a very interesting urban caravanserai was excavated, etc. New materials were obtained concerning civil engineering. The archaeological objects and materials, which were found, point to a high-level of material and spiritual culture of the city people in the IX-XIII centuries. These are wonderful glazed ceramic wares, goods made of glass, and items of toreutics, adornments made from various semiprecious stones and metals, chess pieces and coins. At the end of the XI century life in the city declines because Ahangaran river, which was feeding the city with water, changes its bed. The residents of the city move to Benakent located right on Syr Darya riverside.

Kharashkent, throughout its history, thanks to the international route was closely linked to and practiced active trade relation with China, nomadic steppe and various cities of Sogd and Ferghana.

From Khodjent, main route of the Great Silk Roads went to the West, and through Khavas, Zomin and Jizzakh caravans reached the city of Samarkand (the capital of Sogd), which justifiably received the title of “The Heart of the Great Silk Roads”. Samarkand throughout its centuries-long history experienced the times of rise and fall, was subject to devastating incursions of foreign invaders. And every time it revived itself, and became more beautiful and magnificent. In the East, since olden times it was called as “The Pearl of Great Worth”, “Image of the Earth”, “Eden of the East”, “Rome of the East”, “The Blessed City”. This is by far not the whole list of epithets of this city. And it received such epithets thanks to its ancient history, high culture, majestic architectural monuments, wonderful goods created by its craftsmen, great scholars and thinkers, special role it played in the lives of Central Asian and world powers of ancient and medieval times, and of course, due to picturesque nature and its gifts. The most ancient cradle of Samarkand is the site of Afrosiyob, located in the northern part of the modern city. Its total area equals 220 ha. Archaeological studies conducted here allowed identifying its age - 2750 years old. Here magnificent palaces of Samarkand rules of early Middle ages, of Samanid and Karakhanid times, a cathedral mosque, large residential complexes, craft centers and many others were discovered and studied. Archaeological objects found here point to a high-level of artistic culture of the population throughout the whole history of the city.

From Samarkand the route of the Great Silk Roads led to another capital city of Mawarannahr, i.e. the city of Bukhara. And the route between these two cities in the medieval times was called as “Shohrukh” or “Royal Route”. Medieval authors noted that the distance between Samarkand and Bukhara represented 37 farsakhs, so caravans could cover it within 6-7 days. The road passed through densely populated territory of Samarkand Oasis. After Samarkand, caravans went to the city of Rabidjan (Rabinjan) and then to Dabusiya and approached to Karmana and Rabati Malik, located right near the steppe. From Rabati Malik the road went through the steppe, passed the towns of Tavavmsark and Vobkent and led to Bukhara. In Bukhara one branch went to the north, to the oases of Khoresm through Varakhsha, another one – to the west, to Poykend, and further – to Merv. Caravans covered the distance from Bukhara to Poykend in one day.

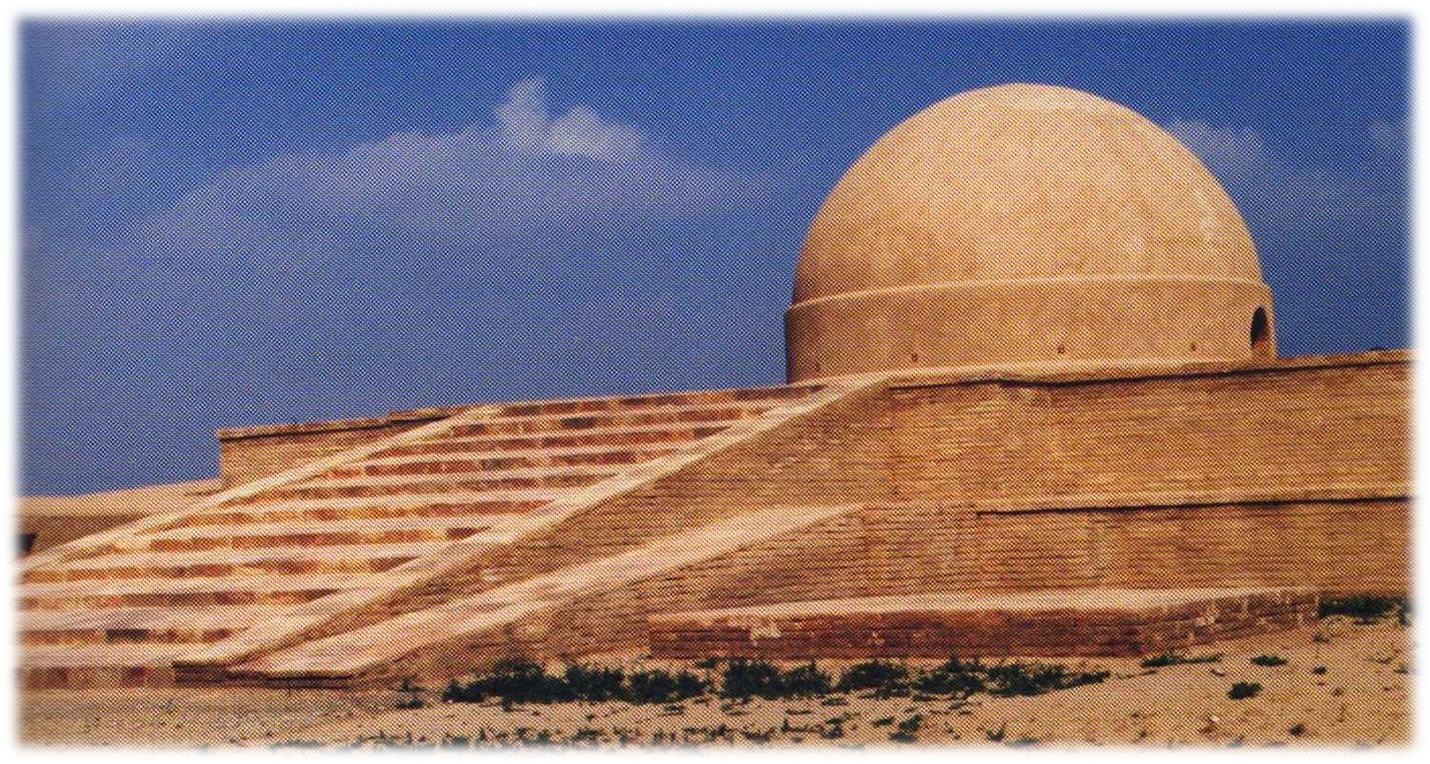

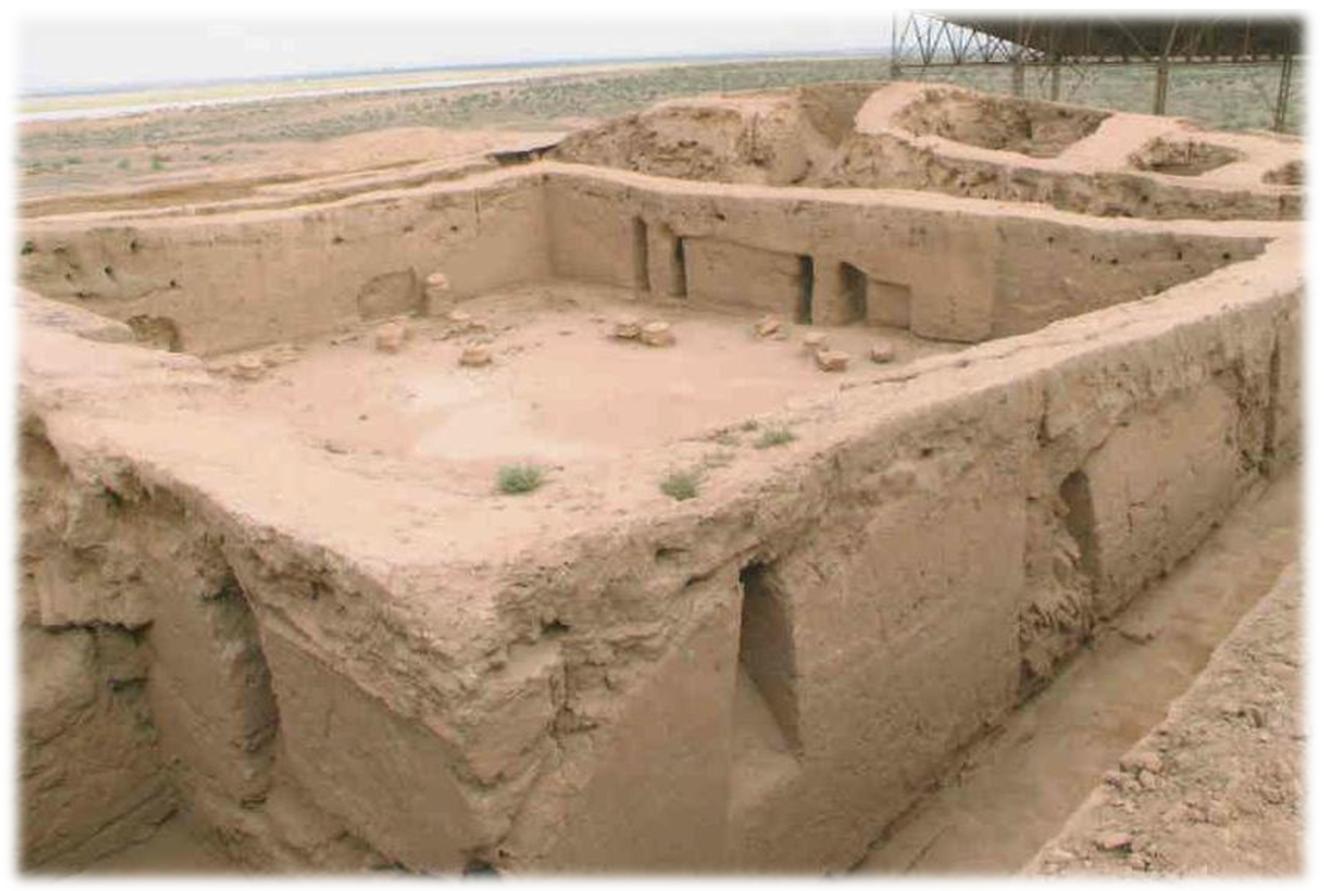

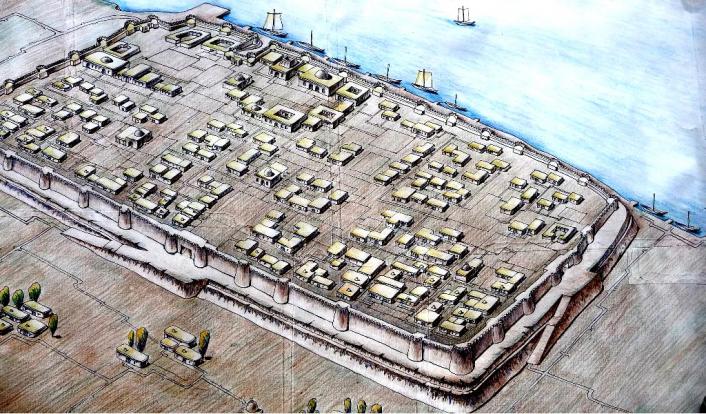

The largest as well as the shortest trade route, which was uniting Bukhara with Merv, passed through Poykend, located on the border with desert areas, 55 km to the south-west of Bukhara (Pic.) Caravans covered this distance in four days (about 20 farsakhs). Ruins of Poykend, in terms of planning structure, represent a rectangle, which stretches from East to West. Total area of the ancient site is 18 ha. Poykend structurally consists of a citadel and two shahristans. Around the city, except for its northern side, there are ruins of many rabads – caravanserais. The citadel with total area of 1 ha is located in the north-eastern part of the city. It was once surrounded by heavily-fortified walls, flanked by projecting towers, and a deep moat. The ruins of the citadel have survived to a height of about 20 m. Shahristan of the city has fortified defensive walls with eight square-shaped projecting towers, which have rectangular loopholes.

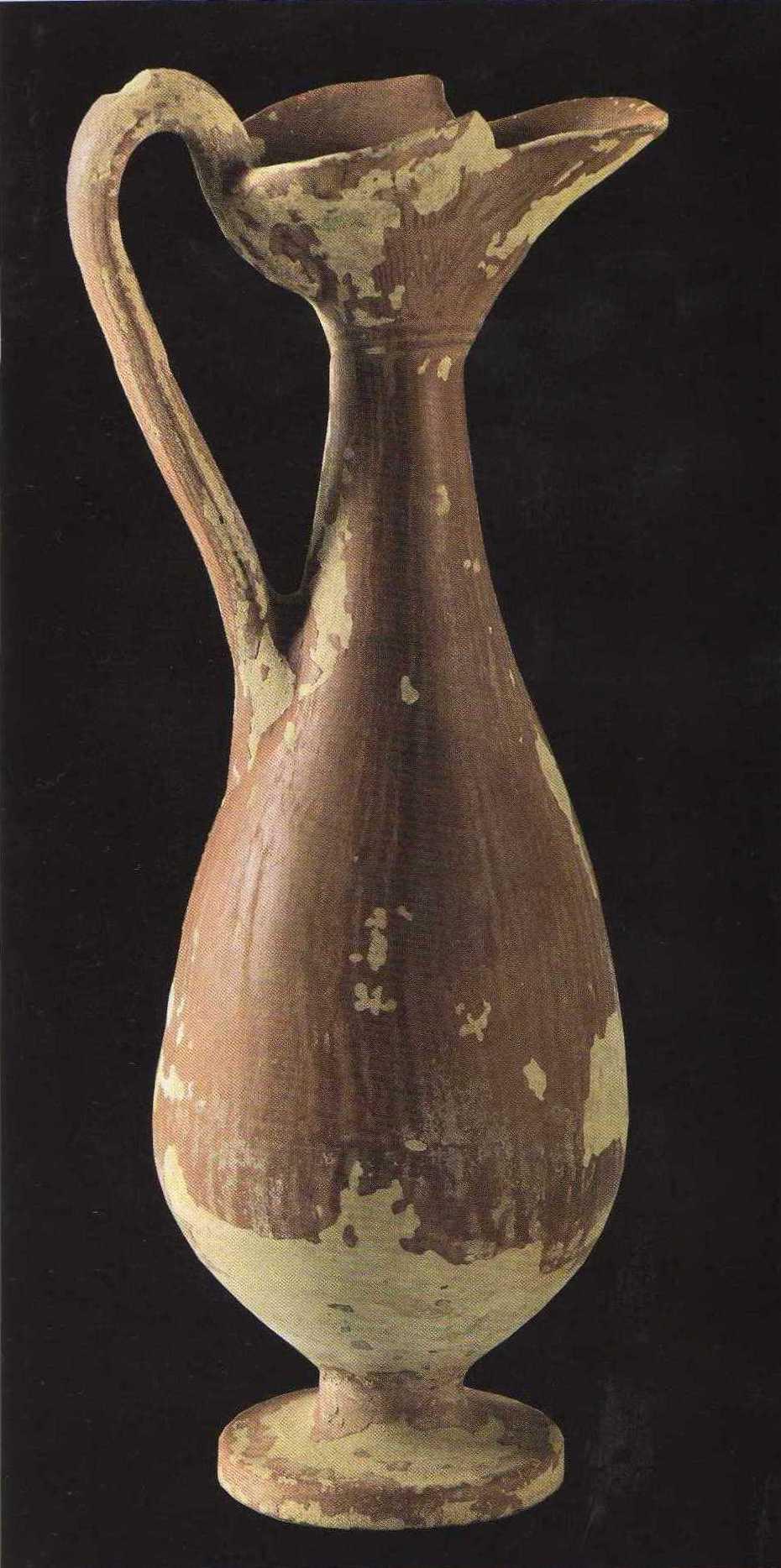

Medieval sources have preserved much information concerning Poykend and its surroundings. Particularly noteworthy is the information provided by Al-Tabari, Al-Maqdisi and Narshakhi. In particular, Narshakhi mentions, that near Poykand there was a large lake, into which Sogd River (Zarafshan River) flowed (Narshakhi, 1966, p.25). Also he informs that all residents of Poykand were merchants. They traded with China, were engaged in maritime trade, and therefore were very rich. Narshakhi also mentions about the epithet, which was given to the city - “Shahristoni roin” (“Bronze Shahristan”). Al-Tabari, Al-Khordarbek and Al-Fakih mention another epithet of the city – “Madina al-tudjor” (“The town of merchants”). The sources have preserved valuable information concerning the history and historical topography of the city. Of particular interest is the information provided by al-Maqdisi, who informs that “Boykent is located near Jayhun (Amu Darya) on the border with the desert; it has a citadel with one entrance, inside it there is a crowded bazaar and a mosque, in the mihrab of which there are precious stones; at its foot there are suburbs (rabad), in which there is bazaar”. (Al-Maqsidi, 1906, pp. 281-282). He also provides a list of goods manufactured in Poykend, which were meant for selling. These were various types of soft fabrics, prayer rugs, copper lamps, horse munitions, sheepskin, fat, etc.

According to the information provided by medieval authors, Poykend was one of the richest cities in Mawarannahr. It is noteworthy that information, which was given in the sources, has been confirmed thanks to the archaeological studies carried out in the ancient site of Poykend. In fact, it is one of the few monuments of Uzbekistan, where continuous investigations have been taking place already for several decades. Plausibly, these archaeological works gained a new momentum and rose to a new level during Independence years. As such, fortification systems of the city were studied, public and residential areas, crafts and manufacturing quarters, caravanserais and many other objects were excavated. All these illustrate peculiarities in the development of city planning of Poykend and its surroundings. Found archaeological objects allowed to reconstruct the life and habits existing within the city at different stages of its existence, especially during the last stage.

The results demonstrate that the first inhabited locality in place of ancient site emerged in the IV-III centuries B.C. Already by the III-II centuries B.C. in place of the settlement a small, relatively well fortified stronghold emerges (Adylov, 1988, p. 38). It appears, that erection of the stronghold in this place is associated with vicinity of caravan routes; with the aim of exercising control over strategically important section, i.e. crossing over Amu Darya, through which goods arrived from west to east and vice versa. The city near river crossing was the resting place for caravans before they journeyed further. And it is exactly this advantageous location of the city that became one of the sources of its economic strength. In the IV-V centuries A.D. the first shahristan of the city gets formed. In the V-VII centuries it includes new territories with emergence of the second shahristan (Muhammedjanov, 1988, p. 187). It bears mentioning that during excavation works, along with ceramic wares, terracotta figurines, items made of iron, etc., Chinese bronze coins of Tan dynasty were found.

The most intensive growth period of the city falls on the Early Middle Ages. It appears that is was due to intensification of relations on caravan routes and strengthening of the role of the city in this process.

At the beginning of the VIII century A.D. Poykend was significantly damaged during Arabs’ campaign to Sogd. The traces of this destruction were clearly identified during archaeological works. The results of these works also demonstrated that the Arab conquest, creation of a large centralized state, the Arab Caliphate, and assuming of power by representatives of local nobility on site, had a positive impact on consequent political and economic life of the city. Poykend within short period of time freed itself and recovered its status. However, defensive walls lost their former importance, as evidenced by the discovery of ceramic workshops and residential houses in place of defensive walls. Ceramic wares and glass items of Poykand in terms of quality and artistic design could compete with those manufactured in various handicraft centers. Here the most ancient drugstore in the whole Mawarannahr was discovered (Muhammedjanov, 1988, p. 89). At the end of the X century A.D. the city gradually declines. Soon the life in Poykend fades away. This was associated with shallowing of Zarafshan River, the water of which, since olden times, had been feeding the city and its surroundings.

One of the active routes of the Great Silk Roads from Samarkand went to the south-west, in the direction of Kesh and near Guzar turned to the south, in the direction of mountainous region, and through the passage of Akrabat reached “Dar-i-ahanin” (“Iron Gates”), where there was a border between Sogd and Bactria. Here there was a border between Kangju and Kushan Empire. From “Dar-i-ahanin” (“Iron Gates”) the road went along Sherobod Darya and led to the city of Sherobod, located on the flatland, from where it went further to the south, to the Valley of Amu Darya and the city of Termez. Termez was one of the most ancient and largest cities of the East.

The city of Termez emerged in the middle of the I millennium B.C. in place of Amu Darya (Oxus) River crossing. It played an important role in the history of many powers of the Middle East, of antiquity and Early Middle Ages. Location of the city on strategically important section of the river and on intersection of trade routes going from north to south, from east to west, facilitated its rapid growth and development. One of the branches of the Great Silk Roads passed through Termez. And the role of the city as an important point, located near the river crossing, was a defining factor in its history. Maybe that is one of the reasons as to why, Termez, even nowadays, is considered southern gates of Independent Uzbekistan.

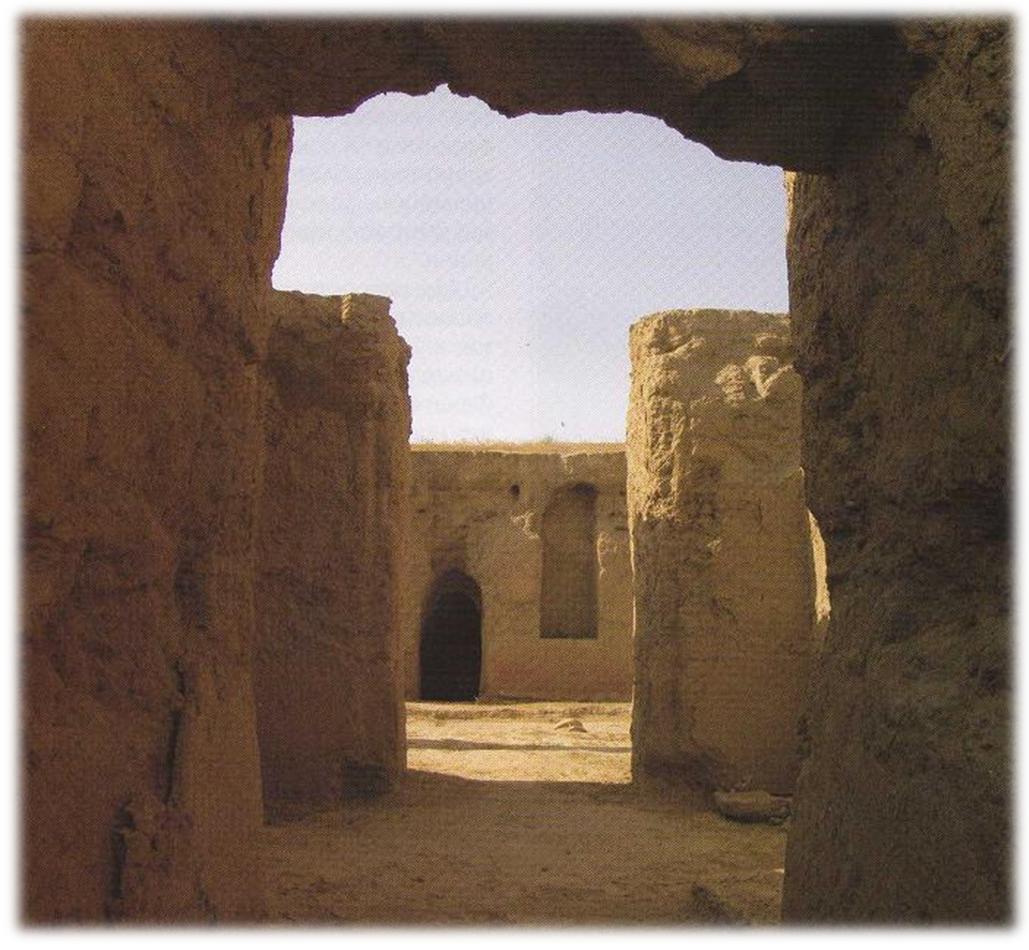

Ruins of Old Termez are located 7 km to the north-west of modern city, along the right bank of Amu Darya River. The ancient site consists of three parts: a citadel, shahristan and rabad. Each of these was fortified with powerful defensive walls. The citadel, or Kuhendiz, was located in the south of the ancient site, right near the bank of Amu Darya River, on the naturally formed sandstone hill. Tall and massive walls of the citadel could be observed from all sides, which point to former strength and greatness of the city. To the north-east of the citadel there was shashristan. Further to the east of shashristan, stretched a huge territory belonging to rabad, where major trade and handicraft centers were located. Unlike other medieval cities of the East, to the east of rabad there was a special territory called “suridikat”, where there was a country residence of Termez rulers of the XI-XII centuries A.D. Total area of the ancient site is almost 500 ha.

The ancient name of the city was Tarmita. The word is derived from ancient word Taramaetha, found in Avesta, and means “the settlement on the other side of the river”. Alexander the Great changed its name to Alexandria on the Oxus. During Seleucid rule the city bore the names of Antioch and Tarmita. In the Armenian sources belonging to the Early Middle Ages, it was known under the name of “Drmat”. Chinese traveler and pilgrim, Xuanzang, who visited the city in 630 A.D., calls it Tami. In Arabic and Persian sources of the IX-XIII centuries it is possible to observe different spellings of its name, such as Tarmiz, Tirmiz or Turmiz.

Medieval sources have also preserved valuable information concerning historical topography of medieval Termez. In particular, authors of the end of the IX century, Ibn Khordadbeh and Ibn Qudamah, inform that Termez was located on the cliff near the river, which washed its walls. Nevertheless, it is Al-Istakhri, who provides the most detailed description of Termez. He notes that the city consisted of a citadel, city itself (shahristan) and suburbs (rabad). He further writes that the palace of the ruler was located inside citadel, the dungeon – in shahristan, somewhere in bazaar. Here was also a cathedral mosque, though Namozgoh mosque was inside rabad. He also mentions that the streets and squares of the city were paved with burnt bricks. The city had a large population, served as a harbor on Jayhun (Amu Darya) River, to which ships from various places sailed. Almost identical information was provided once again by the authors of the XII-XIII centuries. It bears mentioning that the remains of the harbor in the form of a lengthy monumental building, located along southern face of the citadel, with tower-like rectangular projections made from burnt bricks that were laid on waterproof solution (kyr), have been preserved to our days. The projections are located at a certain distance from each other and they form an original bay for ships.

Termez is considered to be one of the most well studied monuments of the south of Uzbekistan. The results of archaeological studies carried out in the ancient site allowed to reconstruct the historical appearance of the city at different stages of its existence. The studies further demonstrated that already by the III-II centuries B.C. in place of Termez there was a big city, which occupied the area of more than 10 ha. It became the main outpost on the northern borders of Greco-Bactrian Empire and was considered one of “thousand cities of Bactria”, as reported by ancient authors. The city represented a large economic and cultural center of Northern Bactria. Here figurines made of ivory and fragments of glass vessels of Egyptian origin were found. This fact allows to conclude that Termez, well before the Great Silk Roads was formed, had had close trade contacts with India and the Mediterranean cities. During the Yuezhi period Temez became the headquarters of the Guishuang tribe, the rulers of which minted the coins resembling tetradrachm of the last Bactrian ruler, Heliocles. In favor of this assumption speaks the abundance of coins of this type, which were found in the ancient site.

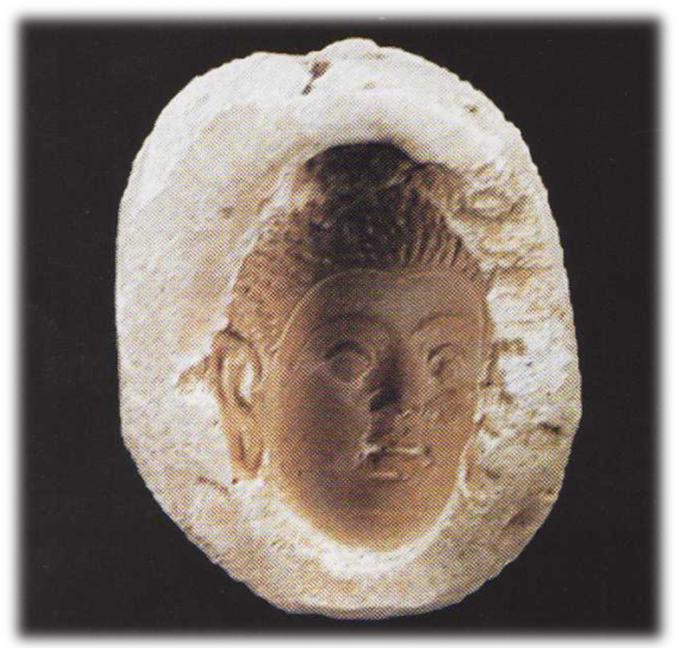

Flourishing of the city falls on Kushan period, i.e. I-III centuries A.D. During this period the city occupies the area of 350 ha. However, in terms of internal housing development it was somewhat dispersed. Numerous monumental buildings of public nature are constructed in the city. In Kushan period Termez becomes the center of Bactria. Many buildings are erected, which are associated with Buddhism. In the north-western outskirts of the city a massive Buddhist center, Qoratepa, gets formed, which unites more than three dozens of temples and monasteries. Not far from Qoratepa another monumental building is erected, i.e. Fayoztepa monastery. The interiors of the monasteries and temples were ornately decorated with murals, stone and clay-ganch sculptures. All these findings are nowadays acknowledged worldwide. And transformation of Termez into the center of Buddhism and Buddhist artistic culture was the result of its becoming part of Kushan state, which created suitable conditions for traveling of Buddhist missionaries in the vast territory of the state and for spreading this religious teaching far beyond India. The objects of artistic culture, which were found in Termez, have direct links with the monuments of ancient India.

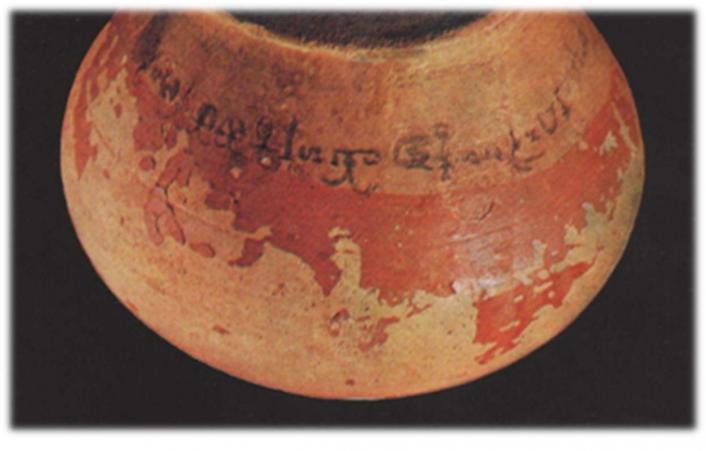

At present there is every reason to believe that Buddhist missionaries were natives of India. In support of this assumption speaks the discovery in Buddhist monuments of Termez of many vessels with inscriptions made in Kharoshti and Brami scripts, which mention about the monks of Indian descent. Later, Buddhist monks in Termez were represented by the natives of Bactria. Chinese historical chronicles preserved the names of many Bactrian missionaries, who played an important role in disseminating Buddhist ideas and Buddhist artistic culture in Eastern Turkestan and China. From among them there were the natives of Tarmita (i.e. Termez). For example, in the medieval Tibetan colophon a famous scholar of Buddhist teachings, Dharmamitra from Tarmita, is mentioned. And there is every reason to believe that Buddhist missionaries from Bactria reached China through the southern branch (route) of the Great Silk Roads.

After the downfall of Kushan Empire the city life falls into disrepair. In the early Middle Ages Termez turns into the center of the small possession, the rulers of which mint coins with the image of the ruler full-face, and on the back side – tamga in the form of an anchor. Probably, by doing so local rulers wanted to tell that the city was still one of the port cities on the Amu Darya River.

The second peak in development of the city falls on the ruling period of the Samanids, Ghaznavids, Seljuqs and Karakhanids. During this time the whole territory of the city was intensively made habitable. Many public and residential buildings were constructed. Though, the center of economic life of the city moves to the territory of rabad. Here richly decorated mosques, caravanserais are erected, handicrafts centers emerge. Total area of the city in that period exceeded 50 ha.

Main source, which ensured flourishing of Termez in the X – beginning of the XIII century was external trade. The author of “Hudud al-Alam” mentioned, that Termez was a trade center of Khutalan and Chaghanian. Termez treasury generated significant income through inter-regional caravan trade. Termez rulers paid great attention to the construction of caravanserais within the city, which were offering their services to merchants and traders. Reconnaissance study of the city demonstrated that caravanserais were concentrated in the territory of rabad. It was here that the remains of more than ten caravanserais were discovered. One of them was fully excavated. Architectural-planning structure of the caravanserai is almost identical to other buildings of this type, which are known in Central Asia. At the same time a peculiar feature of caravanserai in Termez was in the fact that it had special rooms – stores for merchants. According to Al-Maqdisi, Termez exported asafetida, various soaps and ships (Al-Maqdisi ). Asafetida was not only used in medicine. It was also widely used as a vegetable herb in the Middle East and India.

In 1220 Termez was destroyed by Tatar-Mongol troops led by Genghis Khan. According to Juvayni, the people of Termez demonstrated a strong resistance to the invaders. The city assault lasted for 10 days. Maybe because of this brave resistance to the enemies Termez was given another epithet - “The City of Brave Men”.

REFERENCES

- Adylova Sh. T. Stratigraphic excavations in ancient site of Poykand. // Ancient site of Poykand. Concerning the challenges in studying the medieval city of Central Asia. Tashkent, 1988 (in Russian).

- Buryakov Y.F., Bogomolov G.I. // Archaeology of Tashkent Oasis, 2009 (in Russian).

- Muhammadjonov L.R. Conclusion. // Ancient site of Poykand. Concerning the challenges in studying the medieval city of Central Asia. Tashkent, 1988 (in Russian).

- Narshakhi. The History of Bukhara. Tashkent, 1966 (in Russian).

- Descriptio imperii moslemici aucfore Schamsoddin Abu Abdallax Мahammad ibn Axmad ibn abi Bekral-Banna al Basschari al-Mokaddasi. Ed. M.J.de Yoeje, Lugduni:. Batavorum, 1877. Ed.r., 1906 (BGA, III) (in Italian).